It is our aim to make all these titles available to all the fans of Yu music and collectors of Yu editions of foreign performers(Beatles,Queen,Rollingstones,E

SERBIA,BELGRADE,TOPLIČKA BR.35 OPEN MONDAY TO FRIDAY 12.OO-20.OOh,SATURDAY 13.00-18.00 H,TEL.+381117863439, MOB+381698015004

Приказивање постова са ознаком HI FI. Прикажи све постове

Приказивање постова са ознаком HI FI. Прикажи све постове

уторак, 21. јул 2015.

Yugovinyl record shop sale all of the kinds of records from ex Yugoslavia

It is our aim to make all these titles available to all the fans of Yu music and collectors of Yu editions of foreign performers(Beatles,Queen,Rollingstones,E

Yugovinyl record store Belgrade

How the compact disc lost its shine

Thirty years ago this month, Dire Straits released their fifth album, Brothers in Arms. En route to becoming one of the best-selling albums of all time, it revolutionised the music industry. For the first time, an album sold more on compact disc than on vinyl and passed the 1m mark. Three years after the first silver discs had appeared in record shops, Brothers in Arms was the symbolic milestone that marked the true beginning of the CD era.

“Brothers in Arms was the first flag in the ground that made the industry and the wider public aware of the CD’s potential,” says the BPI’s Gennaro Castaldo, who began a long career in retail that year. “It was clear this was a format whose time had come.”

As Greg Milner writes in his book Perfecting Sound Forever, the compact disc became “the fastest-growing home entertainment product in history”. CD sales overtook vinyl in 1988 and cassettes in 1991. The 12cm optical disc became the biggest money-spinner the music industry had ever seen, or will ever be likely to see. “In the mid-90s, retailers and labels felt indestructible,” says Rob Campkin, who worked for HMV between 1988 and 2004. “It felt like this was going to last for ever.”

It didn’t, of course. After more than a decade of decline, worldwide CD income was finally surpassed by digital music revenues last year. With hindsight, it’s clear that technological changes had made that inevitable, but almost nobody had foreseen it, because the CD was just too successful. It was so popular and so profitable that the music industry couldn’t imagine life without it. Until it had to.

In 1974, 28-year-old electronic engineer Kees Schouhamer Immink was assigned to the Optics Group of Philips Research in Eindhoven, Holland. His team’s task was to create a 30cm videodisc called Laservision, but that flopped and the focus shifted to designing a smaller audio-only disc. “There were 101 problems to be solved,” Immink says. Meanwhile, in Japan, Sony engineers were working on a similar project. In 1979, Sony and Philips made an unpredecented agreement to pool resources. For example, Sony engineers perfected the error correction code, CIRC, while Immink himself developed the channel code, EFM, which struck a workable balance between reliability and playing time. “We never had people from other companies in our experimental premises,” Immink says. “It was unheard of. Usually you become foes, but in this case we really became good friends, and we’re still friends after so many years. It was remarkable, actually.”

In June 1980, after complicated negotiations in Tokyo and Eindhoven, the so-called Red Book set standard specifications for the compact disc digital audio format. The story goes that the size (12cm) and length (74 minutes, 33 seconds) were changed at the 11th hour when Sony’s executive vice president Norio Ohga insisted that the disc should have enough space for the longest recorded performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony, his wife’s favourite piece of music, but Immink suspects that is a myth. There were so many technical and financial considerations that it’s unlikely such a key decision came down to one woman’s love of Beethoven.

The CD was introduced to the British public in a 1981 episode of the BBC’s Tomorrow’s World, in which Kieran Prendeville mauled a test disc of the Bee Gees’ Living Eyes to demonstrate the format’s alleged indestructibility. It caught the public imagination, but Immink found the claim puzzling and embarrassing because it was clearly untrue. “We should not put emphasis on the fact it will last for ever because it will not last for ever,” he says. “We should put emphasis on the quality of sound and ease of handling.” (Paul McCartney recently recalled the first time George Martin showed him a CD. “George said, ‘This will change the world.’ He told us it was indestructible, you can’t smash it. Look! And – whack – it broke in half.”)

Advertisement

At least Sony and Philips had their own record labels – CBS and Polygram, respectively – so they pressed ahead. CBS released the world’s first commercially available CD, a reissue of Billy Joel’s 52nd Street, in Japan in October 1982. Philips missed the production deadline so the international release was put back to March 1983. It’s hardly surprising that only 5.5m CDs and 350,000 players were sold that year when so few titles were available.

Faced with low manufacturing capacity and high costs, labels trod carefully. Jeff Rougvie, who later worked for the pioneering CD-only label Rykodisc, was in retail at the time. He couldn’t even order individual titles from Sony, only a predetermined box of six: “A couple of classical titles, a couple of rock titles and Thriller. And of course you’d sell Thriller and the other five would sit around. Labels thought it was an audiophile-only product that was going to sell primarily to classical music buyers. They did not see it as a mass-market format.”

Jon Webster, who worked at Virgin Records between 1981 and 1992, remembers that the label’s first batch of CD releases included Mike Oldfield’s Tubular Bells and Phil Collins’s Face Value: albums likely to appeal to affluent early adopters with the means to buy the discs and the expensive players. The first US CD plant, in Terre Haute, Indiana, debuted in October 1984 with Bruce Springsteen’s blockbuster Born in the USA. Enter Dire Straits.

Aware that most consumers didn’t even know what digital audio was, Sony and Philips had launched a promotional campaign on multiple fronts, including advertisements, public demonstrations, product placement, and special promotions for clubs, bars and radio stations. They also courted studio engineers and artists. While analogue loyalists such as Neil Young and Steve Albini railed against translating music into soulless binary code, some high-profile audiophiles felt that this was how music was meant to be heard. On first hearing a CD, the great Austrian conductor Herbert von Karajan memorably declared: “Everything else is gaslight.”

Dire Straits’ Mark Knopfler was an early convert (the second track on Pure, Perfect Sound Forever, the motley 1982 compilation that came free with early CD players, was Dire Straits’ Once Upon a Time in the West). Knopfler insisted on recording Brothers in Arms on state-of-the-art digital equipment, so a promotional partnership was a natural fit. Philips sponsored Dire Straits’ world tour and featured the band in TV commercials with the slogan, attributed to Knopfler: “I want the best. How about you?”

“Brothers in Arms was an iconic release,” says Gennaro Castaldo. “The CD came to symbolise the so-called yuppie generation, representing new material success and aspiration. If you owned a CD player it showed you were upwardly mobile. Its significance seemed to go beyond music to a lifestyle statement.”

Yet the industry was still half-hearted when it came to back catalogue. Rykodisc (“Ryko” is Japanese for “sound from a flash of light”) realised there was big money to be made from consumers upgrading their record collections to CD if enough care was devoted to remastering, programming (ie, bonus tracks) and packaging. The newcomer made big back-catalogue deals with Frank Zappa and David Bowie because the majors weren’t interested. EMI, which had first dibs, told Zappa: “No one will ever buy your stuff on CD.” “There wasn’t a real good understanding on the majors’ side of what some of this stuff was worth,” Rougvie says.

Eventually, even the slowest labels caught on. When Rob Campkin started work at HMV’s flagship Oxford Circus, London, store in summer 1988, the entire CD inventory filled just five five-foot racks. By the following summer, there were almost 40. “In those days, vinyl was very flimsy,” he says. “Cassettes were completely disposable. When CD came along and said this will last you a lifetime,customers really did lap it up. It felt new, it felt shiny, it felt exciting.”

By the 1990s, the CD reigned supreme. As the economy boomed, annual global sales surpassed 1bn in 1992 and 2bn in 1996, and the profit margins were the stuff of dreams. The CD was cheaper than vinyl to manufacture, transport and rack in stores, while selling for up to twice as much. Even as costs fell, prices rose. “It was simple profiteering,” says Stephen Witt, whose new book How Music Got Free chronicles the industry’s vexed relationship with the MP3. “[Labels] would cut backroom deals with retailers not to let the price drop. The average price was $14 and the cost had gotten down almost to a dollar, so the rest was pure profit.”

Jon Webster bristles at this claim. “What’s fair? The public says. Supply-and-demand says. There were ignorant campaigns by the likes of the Sun and the Independent on Sunday saying that these things cost a pound to make. Well, that’s like saying a newspaper costs 3p to produce. That doesn’t include the creativity and the marketing and the money it costs to make the actual recordings.”

Whether or not the prices were justified, CDs sold in their billions and flooded the industry with cash like never before. This enabled labels to invest more heavily in new talent – Campkin suggests that Britpop might not have happened without the CD windfall – but it also funded misguided A&R frenzies, wasteful marketing and excessive pay packets. “In the 90s we were awash with profitability and became fat, to be honest,” says Webster.

Philips and Sony also reaped extraordinary sums from royalties on the discs themselves, including billions of CD-Roms, although none of it reached Immink and his colleagues. Under Japanese law, engineers were entitled to a cut, but their Dutch counterparts had to settle for a salary and a token one-dollar fee for each US patent they filed. “I’m not saying it happened,” Immink says drily, “but what could have happened is you work with a Japanese guy from Sony and he can buy a yacht and the Dutch guy has to be happy with one dollar.”

Bootleg CDs were a danger the industry could get its head around – you could hold one in your hand. What it couldn’t comprehend was the threat of the MP3: the idea that music could transcend physical formats. “That happened for two reasons,” says Witt. “One was they were enjoying unbelievable profits. Two, the studio engineers hated the way the MP3 sounded and refused to engage with it. A lot of artists hated the way it sounded, too.” What the audiophiles didn’t realise was that most consumers couldn’t tell the difference. “What was the audio experience before the compact disc?” says Witt. “It was cheap vinyl or an AM transistor radio on the beach, and MP3 sounds better than either of those.”

Rougvie suggests a third reason: fierce resistance from retailers who, understandably, considered the MP3 an existential threat. “Distributors and record stores were threatening to return every Ryko title they had, just because we were selling 10 or 12 MP3s every week. If that’s what we were feeling, I can only imagine what kind of pushback EMI or Warners were getting.”

Just like their predecessors in Greece in 1982, 90s executives were too busy worrying about the next quarter to consider the next decade. The status quo was perfect, until it wasn’t. “My biggest bugbear about this industry is that they all think short-term,” says Webster. “Nobody ever thinks long-term. All these executives were sitting there being paid huge bonuses on increased profits and they didn’t care. I don’t think anyone saw it coming. I remember the production guy at Virgin saying, ‘In a few years, you’re going to be able to carry all the music you want around on something the size of a credit card.’ And we all laughed. Don’t be ridiculous! How can you do that?”

Only a handful of people predicted the CD’s downfall way back in 1982. German computer engineer Dieter Seitzer, the forefather of the MP3, immediately considered the CD “a maximalist repository of irrelevant information, most of which was ignored by the human ear,” writes Witt. If music could become digital data, he thought, it wouldn’t be bound by the Red Book. Webster remembers one industry Cassandra, Maurice Oberstein – who ran CBS and then Polygram in the UK – making a similar point. “He was the only one who went: ‘We’re making a huge mistake. We’re putting studio-quality masters into the hands of people.’ And he was absolutely right in that respect. Once you made a CD with ones and zeroes it was only a matter of time before that was converted into something that was easily transferable.”

The fall of the CD, like its rise, began slowly. When file-sharing first took off with Napster in 1999 and 2000, CD sales continued to ascend, reaching an all-time peak of 2.455bn in 2000. Tech-savvy, cash-poor teenagers stopped buying them but most consumers didn’t want (or know how) to illegally download digital files on a slow dial-up connection. So the market remained steady, artificially buoyed by aggressive discounting.

It was the 2001 launch of the iPod, an aspirational premium product which made MP3s portable, that turned the tide. “Before that the MP3 was an inferior good,” Witt says. “Once you had the iPod, the CD was an inferior good. It could get cracked or lost, whereas MP3 files lasted.” Not pure, not perfect, but sound for ever.

The compact disc has proved surprisingly tenacious. It still dominates markets such as Japan, Germany and South Africa; it makes for a better Christmas present than an iTunes voucher; and it has some hardcore enthusiasts. Jeff Rougvie is even planning to set up a boutique CD label to reissue rare and out-of-print albums. “It defies conventional wisdom but so did Ryko at the time. There’s an audience.” But, insists Stephen Witt: “It’s dying. It will go obsolete like the floppy disc did. It just always takes a little more time than you’d think.”

Rob Campkin recently opened a record shop in Cambridge called Lost in Vinyl. He only stocks a handful of the discs that were once the most lucrative product in the history of music. “Margins are very slim,” he says. “I’d have to sell three or four CDs for every one copy on vinyl. It wouldn’t be worth my while.”

How Music Got Free by Stephen Witt is published by Bodley Head on 18 June.

The 12 Best Things In Belgrade, Serbia Every Music Fan Should Do

28 Mar 2014 / Corey Tonkin

Serbia’s most recent difficult history dates back to the 90s where the country suffered through the initial ramifications of the breakup of Yugoslavia, civil war, high inflation and high unemployment rates.

For some reason the Western world’s idea of Serbia hasn’t fully moved on from that turbulent period.

Despite this Serbia’s local music and arts scene has flourished in the years since.

When the 1999 NATO bombs dropped down on Yugoslavia Belgrade still managed to have its own huge outdoor concerts in city squares and on bridges, just as the city’s nightclubs started operating during the daytime.

With that period behind them, Belgrade may not be as architecturally as splendid as its European counterparts, but its nightlife rivals all.

There are countless nightclubs citywide and on the metropolis famous splavs, that is music venues on barges for the uninitiated.

Nightclubs reverberate everything form house music to progressive, tech house and Serbia’s own turbo-folk, which incorporates folk music with electronic and pop elements.

While a wide variety of other genres are represented across the board, there’s an underground scene that has emerged from the scars of the past.

Canadian bred, but Serbian born producer Ensh takes The 405 through his birth place’s music scene, detailing a “myriad of small clubs, cultural centres and re-appropriated spaces. Like Fest, KC Grad and Inex Film”.

Primarily though he introduces outsiders to an establishment called BIGZ, which is an multilevel abandoned publishing house that has been transformed into a creative centre for artists.

The building is home to underground venues, practice spaces and recording studios.

Ensh’s most interesting statement though, is where he describes the artists that make up the creative scenes in Belgrade.

“No one involved in the Belgrade alternative scene plays music because they have any pretense of “making it”, they just want to play music. It is that very same passion that has drawn in DIY tours from all over Europe to Belgrade. It just feels like the right place to be. There is a combination of naiveté, devotion and wonder that would give any musical cynic a glimpse of hope.”

As both Ensh and the city’s large number of thriving nightclub’s demonstrate Belgrade’s music scene is thriving on a number of fronts.

Whether you’re interested in dancing the night away or immersing yourself into avant-garde culture the Serbian capital is one of Europe’s must-visit music destinations.

Read on for the 12 things every music fan must do in the Serbian capital.

Experience Exit Festival

Having

just won the ‘Best Major European Festival’ award at the 2014 EU

Festival Awards, Serbia’s biggest music event is continually recognised

as one of the greatest music festivals in the continent. Despite it

being held outside of Belgrade in Novi Sad the event is too integral to

the country’s music scene not to be included here. Its foundations are

important to note as well. Founded in 2000 as a student movement

fighting for democracy, it still to this day is an important promoter of

social equality. Held over four days Exit books big name acts such as

Arcade Fire, Portishead, Guns N’ Roses, Bloc Party, Faith No More, Lily

Allen, The Prodigy, Arctic Monkeys, Sex Pistols and Pulp to name just a

few.

Having

just won the ‘Best Major European Festival’ award at the 2014 EU

Festival Awards, Serbia’s biggest music event is continually recognised

as one of the greatest music festivals in the continent. Despite it

being held outside of Belgrade in Novi Sad the event is too integral to

the country’s music scene not to be included here. Its foundations are

important to note as well. Founded in 2000 as a student movement

fighting for democracy, it still to this day is an important promoter of

social equality. Held over four days Exit books big name acts such as

Arcade Fire, Portishead, Guns N’ Roses, Bloc Party, Faith No More, Lily

Allen, The Prodigy, Arctic Monkeys, Sex Pistols and Pulp to name just a

few.Visit A Splav

Splav literally translates to raft in English, although it’s known more for being a barge restaurant than a floating device. These restaurants are typically located along the Sava and Danube rivers, which define the city. Most turn into nightclubs by night with no cover charge on entry. The music at the splav’s range from folk, pop and rock acts to dance inspired DJs. You can’t visit Belgrade without hopping aboard at least one of these floating restaurants or nightclubs.

Pick up a record at Yugovinyl

Toplička 35 Zvezdara

Toplička 35 ZvezdaraA favourite amongst locals this record store is true to its name. Selling a variety of vinyl from ex Yugoslavia with titles from major and minor labels Yugovinyl provides a fascinating insight into the music of Yugoslavia. There’s even Yu editions of international legends such as The Beatles, Queen, The Rolling Stones and Elvis Presley.

Witness Svi Na Pod! Live

At the forefront of the ‘New Serbian Scene’ – a collective of pop/rock artists formed after the year 2000 – this seven-piece outfit has a large following in the ex-Yu region. With their name translating to ‘Everyone One The Floor!’ it’s not hard to distinguish just what the band’s dancefloor aims are. The pop ensemble were voted best band in their local music scene in 2009 and were awarded best local concert in 2011 by Serbian website Popboks

Have a late night at 20/44

Toplička 35 Zvezdara Sava River dock

Toplička 35 Zvezdara Sava River dockIf there’s any splav nightclub you should visit first it’s this one. Situated on the banks of the Sava River 20/44 is open all year round. The sound system echoes a broad range of sounds from Detroit techno to soul, disco, funk, house and dubstep. The venue is most famous for its ‘Disco Not Disco’ nights which allows the city’s best DJs to experiment and surprise their audience. Its cheap entry and you can also get a pretty great view of old Belgrade from the splav in summer.

Take A Walk Down Skadarska Street

Tourists venture down this street because it is filled with quality restaurants and cafes in the heart of old Belgrade. Paved with cobblestones and characterised by buildings with impressive murals you won’t remember a more lively daytime Belgrave than when you’re down Skadarska. You’ll also experience plenty of live bands and string orchestras along your walk. Just remember to stop off for some Serbian cuisine while your walking down this pedestrian street.

Buy vinyl from The Wall

The Wall, Balkanska 29 Toplička 35 Zvezdara

Toplička 35 ZvezdaraWhile this record house has no online presence to speak of it’s more than worth checking out in person. Centred towards metal, punk and rock it sells vinyls from these genres at pretty competitive prices. Band merchandise such as hoodies and t-shirts are also for sale here, along with badges and other forms of memorabilia. The Wall is open Monday to Friday from 12pm to 6pm and is located on the first floor of a mini shopping mall.

Catch Gramophonedzie At One Of His Local Shows

Known internationally as the maker behind ‘Why Don’t You’ which reached the #12 spot in the UK charts, Marko Milićević is one of Serbia’s most famous DJs. The producer has released a wide array of DJs and a string of singles to follow up the success of ‘Why Don’t You’, won a European MTV award and played festivals across the continent.

Australijski sajt preporučuje muzičku scenu Srbije

Srbija po svemu sudeći postaje popularna destinacija Evrope za ljubitelje muzike, pa je tako nedavno i australijski sajt ToneDeaf objavio vodič za obilazak Beograda.

tonedeaf.com.au Izvor:

Beta / Emil Vasev

"Poslednji teški periodi u istoriji Srbije počeli su devedesetih, kada je ova država prošla kroz raspad Jugoslavije, građanski rat, veliku inflaciju i visoku stopu nezaposlenosti.

Iz nekog razloga, predstava Zapadnog sveta o Srbiji nije se mnogo pomerila od tog turbulentnog vremena.

Uprkos svemu tome, lokalna muzička i umetnčka scena u Srbiji je cvetala u godinama koje su usledile. Zašto njen noćni život i dalje nije poznat poput onog u Parizu i Londonu, nikom nije jasno, ako imate u vidu da je čak i devedesetih Beograd uspeo, ne samo da održi groznicu klabinga, nego je i značajno ojača.

Kada su 1999. NATO bombe pale, Beograd je i tada održavao ogromne koncerte na gradskim trgovima i mostovima, a noćni klubovi radili su i danju.

Sada kad je to vreme iza njega, Beograd možda arhitektonski ne može da parira drugim evropskim prestonicama, ali njegov noćni život, svakako može.

Postoji bezbroj noćnih klubova u gradu i na čuvenim splavovima, za neupućene, klubovima na baržama.

Sluša se sve od hausa do progresiva i srpskog turbo folka, koji objedinjuje folk muziku sa elektro i pop elementima.

Iako je zastupljen i čitav spektar drugih žanrova, postoji i "underground" scena iznikla iz ožiljaka prošlosti.

Kanađanin rođen u Srbiji, producent Ensh opisuje muzičku scenu njegovog rodnog grada kao "niz malih klubova, kulturnih centara i readaptiranih prostora, poput Festa, KC Grada i Inex Filma".

Pre toga on na svom sajtu The 405 predstavlja BIGZ, kao napuštenu izdavačku kuću na više nivoa koja je transformisana u kreativni centar za umetnike.

U zgradi se nalaze razni prostori za probe, studija i klubovi.

Njegovo najinteresantnije zapaženje odnosi se na umetnike koji čine kreativnu scenu Beograda.

"Niko ko ima veze sa alternativnom scenom u Beogradu ne čini to zato da bi 'pravio muziku'. Oni samo žele da sviraju. To je ona ista strast koja privlači muzičare iz cele Evrope u Beograd. To deluje kao pravo mesto za takve ljude. To je kombinacija naivnosti, posvećenosi i radoznalosti koja bi najvećem muzičkom ciniku ulila tračak nade".

Kako to Ensh i veliki broj noćnih klubova pokazuju, beogradska muzička scena egzistira na brojnim frontovima.

Bilo da ste zainteresovani za ples ili želite da se utopite u avangardnu kulturu, prestonica Srbije je jedna od obaveznih evropskih muzičkih destinacija.

Pročitajte šta svaki ljubitelj muzike mora uraditi u Beogradu.

Odlazak na Exit festival

Foto: PR Exit

Uprkos tome što se organizuje u Novom Sadu, a ne u Beogradu, ovaj događaj je toliko integrisan u muzičku scenu zemlje, da ga ne možemo izostaviti. Njegovi počeci su takođe važni.

Osnovan 2000. kao studentski pokret koji se bori za demokratiju i danas je važan promoter društvene ravnopravnosti.

Održava se u trajanju od četiri dana i do sad je ugostio velika imena poput Arcade Fire, Portishead, Guns N'Roses, Bloc Party, Faith No More, Lily Allen, The Prodigy, Arctic Monkeys, Sex Pistols i Pulp.

Posetite splav

Kupite ploču u Yugovinyl-u

Slušajte Svi Na Pod! uživo

Ostanite do sitnih sati u 20/44

Ovde možete čudi razne vrste zvuka, od Detroit tehna, do soula, diska, fanka, hausa i dabstepa. Mesto je najpoznatije po "Disco Not Disco" večerima kada dozvoljava najboljim gradskim DJ-evima da eksperimentišu i iznenade publiku. Ulaz je jeftin, a leti pruža i divan pogled na stari Beograd.

Prošetajte Skadarskom ulicom

Foto: ZeWaren / Flickr.com

Takođe, možete da poslušate mnoge bendove i tamburaše. Ne zaboravite da poručite i neki specijalitet srpske kuhinje dok prolazite ovom pešačkom ulicom.

Kupite ploču u The Wall-u

Slušajte lokalni haus u klubu Sound

Najbolji beogradski DJ-evi i neke strane zvezde takođe su nastupali ovde. Uprkos tome što se ovde sluša haus, ovo je mesto više klase, pa se potrudite da se lepo obučete, kako biste ovde ušli.

Navratite u Kulturni centar Grad

Od nekadašnjeg skladišta iz 1884. preuređeno je u multifunkcionalnu zgradu u kojoj se održavaju izložbe, koncerti, debate, performansi, konferencije i radionice.

Stand up people: Gypsy pop songs from Tito’s Yugoslavia

November 6, 2012

Following a successful Kickstarter campaign, the historical

compilation of hard-to-find Roma pop classics is set for release in

2013For the past year, British music aficionados Philip Knox and Nat Morris have been indulging in a dulcet love affair with a relatively obscure pop culture niche. After stumbling upon a bootleg copy of ‘Romano Horo,’ an early 1960s single by Esma Redzepova (the self-proclaimed ‘Queen of the Gypsies’), these two star-crossed music junkies fell head over ears in love with Roma pop music from the former Yugoslavia.

This long-distance love triangle spawned a journey to the former Yugoslav republics to recover the endangered gems from the jaws of oblivion and preserve them for future hip-twisters and head-bobbers.

Beginning in the 1960s and lasting until around 1980, this particular breed of pop music flourished in Tito’s Yugoslavia, where Roma culture was able to collide with contemporary European and American influences. Feeding off these and other diverse sources, while keeping their feet grounded in the rich and colorful Roma heritage, these Gypsy virtuosos spun some dainty delights, music as tight now as it was forty odd years ago.

The emotional range and talent of these artists will send you on a journey of self-discovery: you’ll cut the rug to some sylvan accordion keys, weep relentlessly to the swoons of tragic lovers, and maybe even find your next favorite morning bus ride foot tapper. In short, Tito’s Roma rockers give Fleetwood Mac a run for their money.

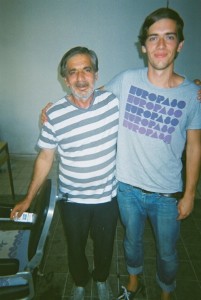

Philip Knox and Nat Morris with the legendary Esma Redzepova. Note the multiple portraits of herself in the background.

After collecting their euphonic booty, the duo ran a successful Kickstarter campaign to fund the release of a compilation of the music they collected, the result of their yearlong adventure. Now we can all feast our senses on the visceral wealth they brought back with them.

In the meantime, Knox sat down to answer some questions about his wacky escapades:

What is it about Roma music that got you jazzed up in the first place?

Roma music is incredibly diverse, with different regions fusing and incorporating different musical traditions. Nat and I had always been interested in the Balkans, and there were lots of great Roma bands from the region who had broken through to the UK: Koçani Orkestar, Fanfare Ciocārlia, Mahala Rai Banda. They’re all amazing. I suppose part of the reason that the ROma have such a great musical tradition is that they were exlcluded from mainstream jobs for such a large part of their history. But, also, music really is a central part of life for Balkan Roma.

I suppose part of the reason that Roma music has become a global success is its rawness and passion. But it’s also about subtlety and control, it’s about tone. That’s what makes it so compelling.

While traveling through the Western Balkans did you ever get lost in translation? If so, do you have any stories to tell us?

Many times. Everywhere we went we would ask people about old and often forgotten Roma singers and instrumentalists, about where we could find ploča gramafonska (vinyl records), or for directions to a buvlijak (fleamarket). Although we found a couple of great record stores and collectors, for the most part peole thought we were insane. Kind-hearted people would tell us to wait while they brought us an MP3 CD of all the Roma music we could want, and it coudl be hard to explain that we wanted the vinyls because those songs couldn’t be downloaded.

Our worst case of lost-in-translation blues was when tried to hitchhike from Belgrade to Sarajevo. We had to be in Sarajevo in two days for meetings, but we were broke. We hitchhiked as far as Northern Bosnia on the first day, and were told that we could get a short bus ride to a place where there were cheap coaches to Sarajevo. We asked the driver to drop us there, a crossroads of tiny mountain tracks with a petrol station. The arsehole of nowhere. The guys in the petrol station were the first unfriendly people we’d met on that trip.

We eventually convinced them to call us a taxi to the nearerst place to stay – the taxi was their friend, a tattoo artist whose car had no back seats. The hotel, in Milica, was owned by a mining franchise, with framed pictures of mining machinery everywhere and a huge statue of Vladimir Putin in the town square. We were only a few miles from Srebrenica. Dark times.

Anything interesting to eat or drink while abroad?

I love Macedonian food. Lots of amazing tomatoes and aubergines and garlic. One day in the market in Skopje we bought a delicious hard sheep’s cheese and had it on bread with black honey from bees fed only on tea flowers. One of the best meals ever.

As far as drink goes, I have a weakness for rakija. The best stuff is always made at home, and of all the home-brews we tried, my favourite was made by the grandfather of the owner of Yugovinyl, a brilliant little record shop in Belgrade. When we whent there to check out his record collection he plied with the stuff until the bottle was empty. This is probably why we bought so many records there.

What was the funkiest smell you encountered? How about your worst bathroom experience? Give us the scoop on your poop.

The worst smell in the Balkans is the stink of bullshit coming off most of the politicians. We were in Macedonia for its national holiday last year, where they unveiled an enomrous and obscenely expensive bronze statue of Alexander the Great in the town square.

Meanwhile, up the hill in Šutka, the biggest Roma settlement in the world, there are still huge infrastructure problems, bad roads and rolling blackouts. Of course, Alexander the Great wouldn’t be a political bargaining chip for the nationalists if it weren’t for Greece blocking Macedonia’s claims to be called Macedonia or associate itself with anything that might be considered Macedonian. Corruption is rife in Serbia, Bosnia, everywhere, and people’s lives aren’t getting any easier. Very stinky indeed.

They say nightlife is pretty wild around these parts. Tell us about your craziest nocturnal romp with the Romas.

We had an amazing night in Crni Panteri [Black Panthers] in Belgrade. It’s a live music venue right on the Sava – but it feels like it could be in deepest Mississippi. Most of the staff and musicians are Roma, though they don’t always like to openly self-identify as such.

On the weekends they mostly play Serbian folk music, always a crowd pleaser, and people are dancing on the tables by midnight.

We went another time, mid-week, where the vibe was much more intimate but very raw. We stayed still five in the morning chain-smoking and drinking with the owner and roaring along the words to Roma music classics from the region – the players really weren’t holding back.

At one point a massive motor yacht turned up and docked beside the bar and all these young Serbians jumped in. Everyone was sharing the fun and the love of the music. It was a great night.

*More info: standuppeople.co.uk

петак, 13. јул 2012.

STOCK vinyl in Novi Sad, Saturday, July 14

Hundreds of collectors from Serbia and abroad have visited the Stock Exchange of gramophone records in Novi Sad. Market takes place every first Saturday, but this time he moved for a week and visitors to EXIT was able to visit.

We invite collectors playing records, CD singles and the original editions, fans of forgotten vinyl , to come and see what it is that attracts collectors from all over Serbia to come to Novi Sad.

Free admission!

Ознаке:

CAFE,

GRAMOFON,

GRAMOFONSKA PLOCA,

HI FI,

KAFE SONJA,

NOVI SAD,

RECORD,

RECORD FAIR,

SERBIA,

STORE,

VLADIMIRA PERICA 3,

YUGOVINYL

уторак, 22. мај 2012.

Пријавите се на:

Коментари (Atom)

It is our aim to make all these titles available to all the fans of Yu music and collectors of Yu editions of foreign performers(Beatles,Queen,Rolli